Mies vs. Stirling in London

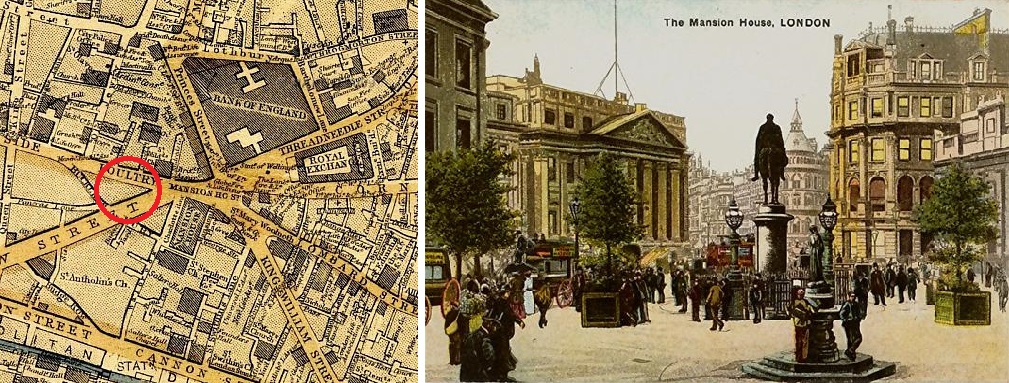

/Last month I visited the exhibition Mies van der Rohe and James Stirling: Circling the Square, at RIBA's Architecture Gallery. It was meant to illustrate the contrasts between two schemes for Mansion House Square, one of London's most prominent sites (see below). It also raised some much bigger questions.

Mies' design, developed between 1963-69, offered London a glass tower and a large empty gridded public space---typical Mies but quite unusual for London. It was not built. Stirling's project, called Number One Poultry and designed between 1985-93 on a more modest footprint, was built and stands as an exemplar of Postmodern architecture (right below). The RIBA exhibit featured a large model of Mies' design (left below), dozens of sketches and drawings from Stirling, and many period documents about the political machinations that unfolded.

Left: RIBA exhibit. Right: Number One Poultry. Photos by Anthony Denzer

Part of the importance of the RIBA exhibit is that Mies' design is not well known. As Jack Self wrote in The Guardian:

"every architect over 40 in Britain has a strong opinion about the work. And yet these views are often held with almost no knowledge of what was actually designed as very little information about the work has existed in the public realm, until now."

A major strength of Mies' design, which has gone unnoticed I think, was its attention to the nearby church of St. Stephen Walbrook, a masterpiece by Sir Christopher Wren. In the model photo below, you can see the Wren church at the bottom-left. It would have been given a prominence which today it unfortunately does not enjoy.

Mies van der Rohe's design for Mansion House Square. Image from The Guardian.

Why was Mies van der Rohe's project rejected? Firstly, the politics of public space. Self's Guardian article cited above also includes some excellent historical context about the "tumultuous" political atmosphere in London in the Thatcher era. Mies' monumental public space would certainly harbor political protests. This could not be tolerated, Self concludes, so the Mies project was killed.

Secondly, Prince Charles inserted himself in the process. In 1984, 15 years after Mies' death, Mansion House Square was still under consideration. Then the Prince of Wales gave a famous speech (which the RIBA curators displayed), including his view of the Mansion House plan:

"It would be a tragedy if the character and skyline of our capital city were to be further ruined and St Paul's dwarfed by yet another giant glass stump, better suited to downtown Chicago than the City of London."*

Was Prince Charles later satisfied with the Postmodern replacement? No. In his book A Vision for Britain (1989) he said Stirling's design "looks rather like an old 1930s wireless." And, in reference to the platforms pictured above, he asked: "Is somebody proposing to dive from this tower?"

Instead of a monumental plaza, Stirling's building has a rooftop restaurant/bar, and an observation deck with plastic grass (see below). On a warm June Friday evening, I went there to see the site from above and reflect on what I'd learned at the exhibit. The rooftop was packed with young professionals enjoying not only their beverages but also, clearly, the building and its spaces, as well as the transformation of London in the background. I realized that RIBA mounted this exhibit just in time, for a new historical moment when Postmodern isn't a dirty word the way it certainly was a few years ago.

Rooftop terrace at Number One Poultry. Photo: Anthony Denzer.

In the book London’s Contemporary Architecture: An Explorer’s Guide, Ken Allinson and Victoria Thornton wrote: "One Poultry was already incongruously at least ten years out of fashion when completed."

I expect the RIBA exhibit will raise the profile of Number One Poultry and open the door to a new appreciation for Stirling. But it also revealed the political conservatism that underwrote Stirling's project, and that's something you can't tell just by looking at it or by enjoying a cocktail on the roof.

And finally, was London deprived of a great building and a great public space? Naturally, the RIBA exhibit implicitly raised that question but made no explicit attempt to answer it. In my view, a moment of some relief from the congestion and visual chaos, as Mies projects provide, would be welcome in the Bank district. (This is partly why Wren's city church interiors are so pleasurable.) Moreover, as a record of architectural history, London has few great high-modernist buildings from the 1950s-60s. So I am inclined to say yes, it was a missed opportunity when Mies' plan was finally rejected.

● ● ●

*Full text of speech here. This was the famous "monstrous carbuncle" speech. In black tie, Prince Charles memorably disparaged a high-tech design by Peter Ahrends for the extension of the National Gallery:

"What is proposed is like a monstrous carbuncle on the face of a much loved and elegant friend." (video link)

In a witty nod to Prince Charles' remark, a British magazine now awards the Carbuncle Cup annually to "the ugliest building in the United Kingdom completed in the last 12 months."